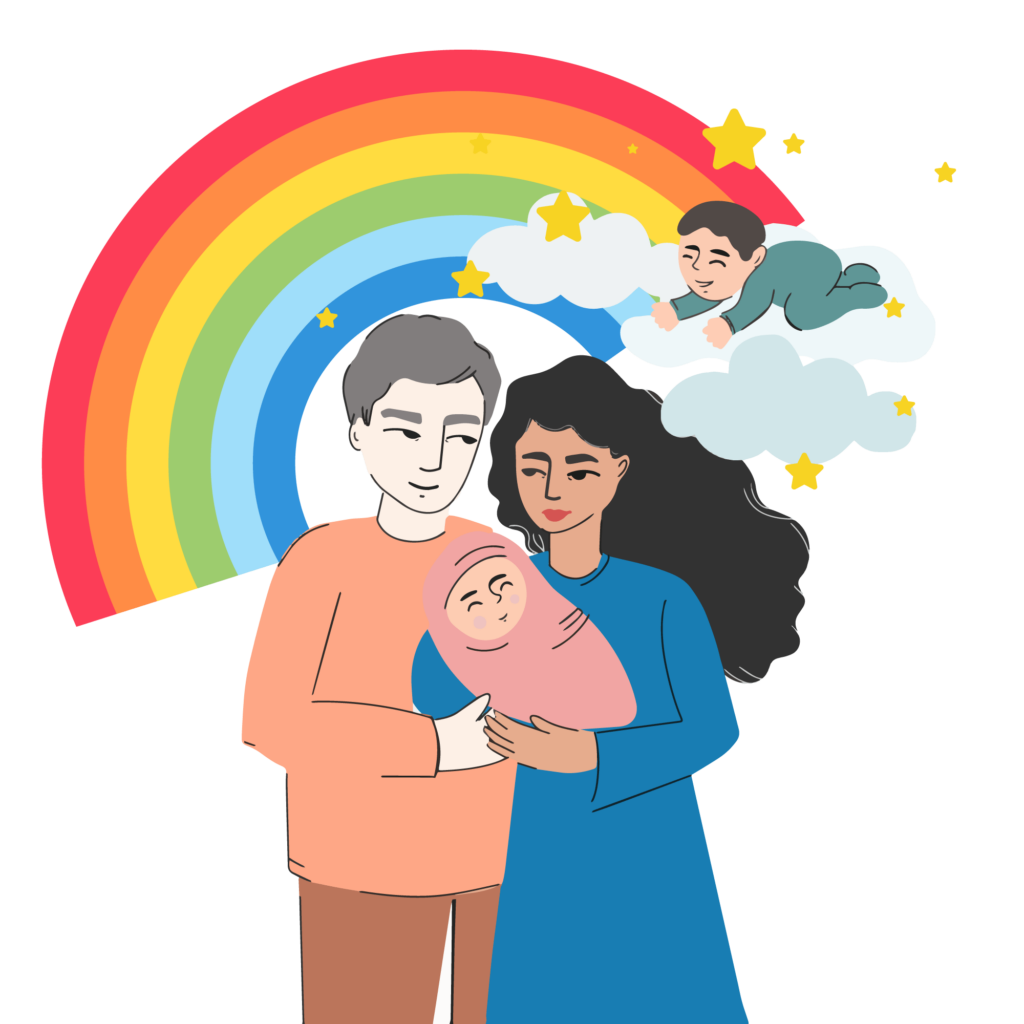

Have you ever heard of a “rainbow baby”? When you first learn this term, it’s hard to imagine that it refers to a tragic event in the past. May explains its meaning.

What is a rainbow baby?

A “rainbow baby” is a child born after perinatal loss. The baby who has passed away is often called a “star baby.” Parents who go through this painful ordeal are called “paranges.”

Perinatal loss affects about 20 to 25% of pregnancies, meaning that a quarter of (future) parents may experience the loss of a fetus in utero or at birth (early or later pregnancy losses, medical terminations of pregnancy, or fetal or neonatal deaths). Those same parents may then begin a new pregnancy, with its share of doubts and hopes, and welcome a rainbow baby.

Why the rainbow symbolism?

The word “rainbow” wasn’t chosen by chance. It refers to the well-known saying “after the rain comes the sunshine.” It’s easy to understand: a baby’s death represents the storm, and the birth of the new child, the sunshine. This sequence of rain and sun creates… a beautiful rainbow. It brings hope after perinatal loss.

While some people find comfort in this term, others do not. The idea of linking bad weather with the star child and of drawing a connection between the two children doesn’t necessarily feel right to everyone. Both reactions are totally understandable, and you should feel free to pick up—or set aside—what helps in your own situation.

How to navigate a rainbow pregnancy after a loss?

Deciding to try for another pregnancy after a perinatal loss isn’t easy; there is no ideal timeline, and each couple will follow what feels right. The child to come is not a replacement child but part of the sibling line, and sometimes plays a facilitating role in processing the previous grief.

This new pregnancy can be very anxiety-inducing; it’s common to see the expectant mother more protective of the baby to come, more anxious. She may have lost some trust in life and need protective markers: more frequent prenatal medical follow-up, checking the baby’s heartbeat or movements… Over time, confidence usually grows in the strong bond that unites them and in her child’s ability to thrive in good health by her side.

Difficult anniversaries mark the parental journey shaken by a perinatal loss: the date of conception, of the loss, of the expected due date. These dates resonate and sometimes overlap between pregnancies and births. Birth preparations may be delayed, for fear of truly believing. Here are several things to do during pregnancy in those difficult moments:

- Talk to the baby during the pregnancy. It’s their story too; they carry this memory in the womb.

- Don’t blame yourself for feeling sad or stressed during pregnancy.

- Seek support to put words to your fears or feelings and find an approach that helps you feel a bit more serene (relaxation, massage, etc.). The previous pregnancy can also become a strength, an asset for the next one.

Birth will be charged with emotion for the parents, who may feel repaired in their role, but also sometimes guilty when thinking of the baby who died and couldn’t share those moments with them. This emotional reactivation is normal and should be considered a conscious and healthy part of the journey.

August 22 is dedicated to rainbow babies; some parents use this date to commemorate their star baby and celebrate their rainbow baby. There is also October 15, Pregnancy and Infant Loss Awareness Day.

What should be considered when choosing a rainbow baby’s name?

The choice of a name is, of course, up to the parents, but it’s generally not recommended to give the rainbow baby the name of the baby who died. Why? Because the child to be born is different from the other baby—another person it’s important to distinguish. They should not feel as if they are replacing someone.

At birth, it’s important to talk to the baby to explain their story and any moments of sadness: “Yes, Mommy is sad, but it’s not your fault. Your arrival fills me with joy, but I’m grieving because before you, we were waiting for your big brother, and he didn’t get the chance to join our family, and I miss him terribly. It’s not your fault; I love you infinitely, and you don’t have to worry about me because I will take care of myself, just as I take care of you.” Talking about it during pregnancy avoids wondering when to do it later and accidentally creating a family secret. The baby doesn’t understand the words, but they do understand the rightness of the truth they feel in their mother’s voice. Finding the right place for this “angel” baby isn’t easy and can take time.

Where can parents of star babies find support?

Loved ones may sometimes minimize and suggest moving on (because it’s not easy to support a grieving person, and it’s simpler to rejoice over a birth). Choosing to talk with trusted people who can truly understand what parents are feeling and/or consulting resource pages on the topic can be very helpful.

Here are several very useful resources to consult on the subject:

- Psychologists, preferably trained in these specific issues…

- Support organizations for perinatal grief (Agapa, SPAMA, Naître et Vivre, Petite Emilie…).

- Social networks (Instagram pages such as: @parlez_moidelle, @aurevoir.podcast, @a_nos_etoiles, @mespresquesrien…).

- Podcasts (Au revoir podcast, Le Tourbillon podcast, Bliss Story, La Matrescence…).

- Sophrology, hypnosis, relaxation, acupuncture, Bach flowers…

- Books on perinatal grief: Je n’ai pas dit au revoir à mon bébé by Catherine Radet, and Traverser l’épreuve d’une grossesse interrompue by Nathalie Lancelin-Huin.

- Books on teaching children about perinatal grief: Je t’aimais déjà by Andrée-Anne Cyr and Bérangère Delaporte, and La petite étoile et l’arc-en-ciel by Valentine Poirot.

- Illustrations by Anne Bourdeau on her Instagram page @korrigane.illustration.

- The website and book Dans ces moments-là.

If you have any questions on the topic, feel free to download the May app, where you’ll find plenty of resources to support you.

Ideally, don’t try to sweep the pain under the rug: take the time to listen to it and not deny it. Caring for it, to help this wound heal rather than trying to forget, is important.

Testimonials from parents of rainbow babies

May offers the stories of two mothers of rainbow babies who generously agreed to open up. In our view, stories shared on this topic are precious because they can help people experiencing perinatal loss feel less alone. Please note, this reading can stir up strong feelings—read these stories only if it feels like the right time for you.

Marie, a mother of three, delivered a star baby vaginally at 24 weeks’ gestation; she tells her whole story in a narrative filled with strength and resilience:

“ My name is Marie, and I am a mom three times over: to my eldest, Gaétan; to a little star, Gabriel; and to Valentine, my rainbow baby.

I’m a pediatric nurse and worked for sixteen years in neonatal intensive care with premature babies. That’s why, when I myself was confronted with perinatal loss, I suddenly found myself ‘on the other side of the gown’.

I supported parents through the process and then the withdrawal of care for their children; I helped them navigate the challenging work of grief because I faced it regularly in my profession and was one of the go-to people in the unit for this.

Living it made me tip to the other side, as a mother, while still keeping my identity as a caregiver.

I became a mother for the first time in 2010, after more than two years of waiting.

Everything went very well, although because of my profession I remained very vigilant about all possible risks at each stage… Occupational hazard…

We decided to wait a bit before having a second child, and we were right, because I became pregnant very quickly with the second pregnancy, which made us happy and reassured.

I felt calm but still stayed vigilant about follow-up.

During the second ultrasound, at twenty-two weeks, the ground fell out from under us when we discovered a brain malformation that left no doubt about the need for a medical termination of pregnancy.

So I delivered vaginally, in April 2013, at 24 weeks’ gestation, an adorable little boy weighing less than 800 grams, whom we chose to name Gabriel to help him take flight…

I remember living it step by step. Very professionally for the practical side, but with much love and sharing with my partner. I knew what was going to happen, what we had to choose, to prepare what mattered to us, to make space for him in our lives, even if his time in our arms was brief.

I remember telling myself, like a mantra, this birth—it will make you stronger; you’ll know yourself even better afterward, and it will help you support your next baby to bring them into life. And I thought this pain could transform and later become a strength to go back and support parents facing this in my unit.

It so happened that during my pregnancy, my two sisters-in-law were also pregnant at the same time as me, with due dates only a few weeks apart. When my nephews were born, it was very, very hard to live through. An upheaval, an intense emotional rift. I was so happy to become an aunt, to meet those babies (they were the first children for our brothers), but I was overwhelmed by the infinite sadness and the deep pain that my baby wasn’t there too…

What we’re very proud of, my partner and I, is how we managed to support our ‘big kid’ (who wasn’t yet three) through this family grief, and how we got through it together, as a couple. We managed to support one another, to listen, to make our way together but also each in our own way. I think the fact that I’m a caregiver and knew exactly what would happen with this medical termination helped me. I had resources to support us. I knew that in a couple, we wouldn’t necessarily have the same timeline or the same feelings in our grief. Even though it was very hard, we’re used to talking daily about our needs, to putting our emotions into words, and that’s what helped us. Of course, we inevitably made mistakes, doing the best we could at times, but we’re happy and at peace, I think, with how we’ve woven this baby into our family story.

There were no secrets for our little two-and-a-half-year-old boy. We used simple, accurate words, answered his many questions every time he had them (and still do to this day). Little Gabriel found a just place within the family—his own, in his uniqueness.

After our baby’s death, I knew I wanted to become pregnant again, but taking the necessary time for it to go well and for us to be ready to welcome this new child properly. This third pregnancy also arrived very quickly once we tried—one year after the previous one. This time we wanted to know the baby’s sex, unlike the other pregnancies, because I needed to project myself, to speak to this baby knowing who they would be, and to reassure myself that I was clearly distinguishing them from my previous baby. I was happy to learn that it was a little girl. At least it was clear: a new pregnancy, a new story, another baby. I was also very happy about my baby’s sex because we would have ‘one of each,’ but I felt guilty about rejoicing in that, with regard to Gabriel who couldn’t live.

I didn’t experience this pregnancy as more stressful or harder than the others. I savored it and still loved being pregnant. I was followed more closely; we were well supported, and just as we had supported my eldest by explaining everything that was happening, I decided that the baby who had died should not be ‘a burden’ for our little girl who was going to be born. So we talked to her very early while she was in my belly, because I still had moments of stress, and I’d tell her, “Don’t worry, it’s not your fault. You should know that before you, there was a baby here who couldn’t live. But for you, everything will go well, and we can’t wait to meet you.” I was supported by a psychologist I already knew—we had done that for the two previous pregnancies—but above all, we did haptonomy again, like before. It really helped us welcome this little girl in the best conditions.

The birth of this little rainbow baby was amazing because it was exactly the one I wanted. For a first birth, you don’t know what you’re heading into; you don’t know the pain you’ll feel, how you’ll cope, you’re discovering your body. So for this third birth, I went in ‘relaxed.’ My water broke in the morning, and I took my time getting ready before leaving. Once at the hospital, we were welcomed wonderfully by teams where several caregivers knew my story (I gave birth where I worked). I gave birth without an epidural, in an incredible moment shared 200% with my partner, eyes locked on his and his hand holding mine. I felt completely in charge of this birth. The midwife arrived at the last minute to catch our baby and help her be born. I felt so strong! I felt that surge of life, that power of a woman’s body bringing a child into the world. I told myself, ‘In the end, life made us go through a terrible ordeal, but the scars from that experience accompanied me to make this birth the wonderful moment it was.’

This rainbow baby is now a nine-year-old girl named Valentine, and she’s doing great! Since she was born, she’s always had her feet firmly on the ground. She loves to clown around; she’s a little ray of sunshine. She knows her story and her brothers’, and we talk about it whenever she feels the need, very serenely. Each child has their own tree in the garden. I often ask myself: ‘Is she like this because she felt she had to be very alive?’ ‘Is that just my interpretation? Would she have been like this anyway?’ We don’t really know, and I think the most important thing is to know how to let go sometimes and not overthink it. In any case, not more than necessary.

The months after birth can also sometimes be a bit difficult even when everything is going well for the baby. There can be things that still need support—resurgences from the previous pregnancy and the grief—and this can feed into or foster postpartum depression. I myself lived through a few months of anxiety and deep sadness at times, and it’s essential to know this can happen and to talk to someone so you don’t stay alone with it. You have to be kind to yourself and not put pressure on yourself about what you feel by saying ‘I shouldn’t be doing this’ or ‘I should feel that’ or ‘this isn’t normal.’

The advice that really helped me after Gabriel’s birth was: ‘Don’t hide your pain; don’t try to sweep it under the rug, because one day it will come back with incredible force. Accept looking it in the face, get help if it’s too hard to live through alone, and walk with it so it can heal gently, over time.’”

Julie, also a mother of three, shares her story with great clarity and honesty:

“I’m Julie, I’m 42, married, and mom to three big boys born in 2009, 2012, and 2016 (rainbow baby). In December 2014, we lost a little girl who was born without life due to multi-organ failure discovered during my pregnancy.

For us, the nightmare began from the very first ultrasound, and the rest of my pregnancy was punctuated by tests, each more invasive than the last. All that suffering waiting for a diagnosis, only to be told at seven months of intrauterine life that she wouldn’t be viable and that her life had to be ended before birth. What she had wasn’t known to any OB-GYN or obstetric specialist—it was ‘bad luck,’ as they say.

Thaïs was born on December 16, 2014, ‘without life.’ There is nothing worse than giving birth to a dead baby. No one can imagine it without having lived it. Our loved ones couldn’t understand what we were going through. The comments from family and friends, full of good intentions, made us crazy and sad. To overcome this ordeal, we also saw a psychologist.

We climbed back up thanks to our children, who left us no choice but to keep hope in life. We started trying for a baby again six months later.

I don’t remember the emotions that accompanied the discovery of my fourth pregnancy. Maybe out of fear of suffering, even though I told myself that misfortune couldn’t strike us twice in a row.

We learned very quickly the sex of our child—it was a boy—so I naturally projected myself into an easy pregnancy without problems, like with the older ones. I don’t remember feeling magic or euphoria. The days went by without me dwelling on my sensations or on my growing belly. My loved ones seemed more enthusiastic than I was; I couldn’t bring myself to rejoice. I can’t say I feared a new problem; each ultrasound didn’t scare me. I was simply suffering from others’ lack of understanding of what we’d lived through, and from their failure to acknowledge our still-present pain.”

Grief has no real end, and a part of a parent may remain in mourning for that child for a lifetime. But that doesn’t mean they won’t be able to shower the next child to be born with love.

This text was translated from French by an artificial intelligence. The information, advice, and sources it contains comply with French standards and may therefore not apply to your situation. Make sure to complement this reading by visiting the May US/UK app and consulting the healthcare professionals who are supporting you.